(A note from 2025: I forgot all about this entry, I guess the fact that it sat unfinished for two years kinda proves it. Reading it back, it’s not very … interesting… but I figure I’ve put the effort in so I’ll hit publish anyway. 🙂

Clearly, I have a thing for the London Underground. I know, it’s weird. Even I don’t know why, but I guess it’s something to do with all its history, imperfections, complexity, silliness, appearances in Dr Who, but despite all that, its effectiveness in doing what it’s meant to do. So let me try to get all this tubism out of my system in a seperate blog entry. (So all the normal people can just skip it and get on with their days :). It will re-hash some stuff I’ve already put in the holiday blog so don’t panic if you think you’ve seen some of it before.

Now I know the tube network is far from perfect, but as tourists we’ve had no issues despite the strikes. No stuck or delayed trains, no issues other than a bit of crowding and even that hasn’t been as bad as Sydney sometimes. I am no doubt always looking at it through rose-coloured holiday glasses, but it has been fantastic every single time in getting us around London, and it’s just a nice place to hang out. It’s weird, I totally don’t get that kind of vibe waiting at Town Hall or whatever, but here, it’s different.

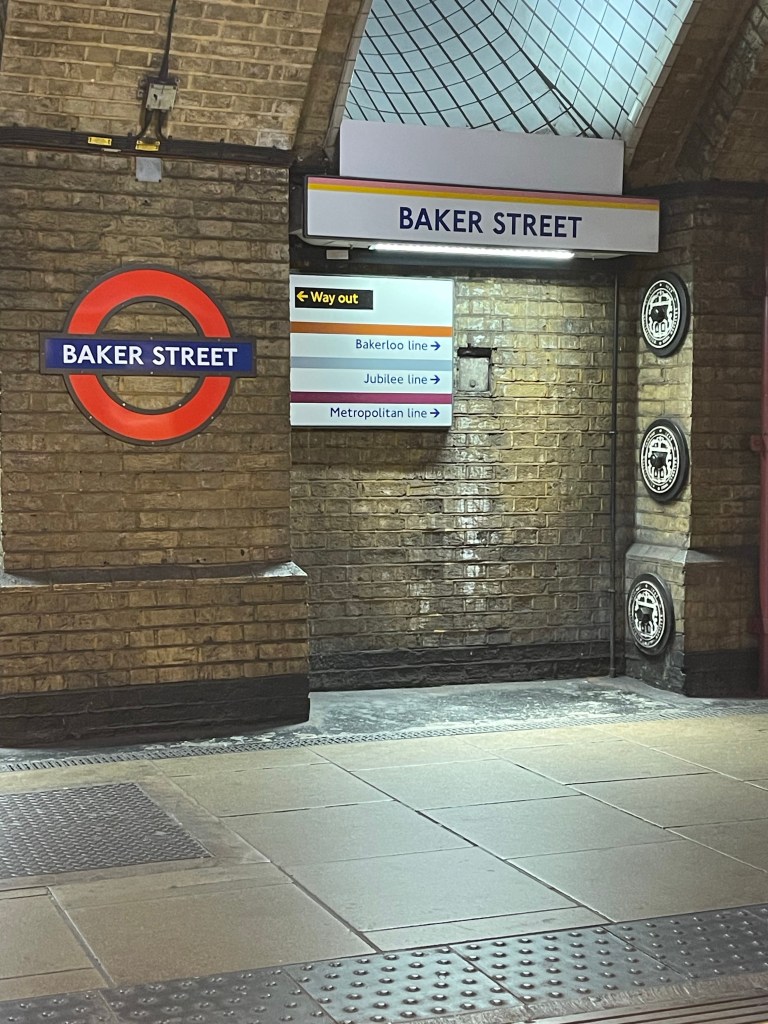

A super-brief history. It all started in 1863, 160 years back, with a little line between Paddington and Farringdon. This first underground line was indeed under ground, but only by a foot or two, mostly built by ripping up roads (and some buildings) , building train lines and stations, and then building a roof back over the top. If you’ve seen that bit of My Fair Lady where the road is all torn up, there you go. The line went from Paddington to Farringdon, about 6km or so. Of course these days Paddington is a huge terminus that looks nothing like it did, but Baker Street (or at least a small part of it) still looks quite similar to how it did back in 1863. All the holes were to let the smoke from the steam trains out – they’ve long since been covered up but overall, between 1863 and 2023, it’s not that different really.

Steam trains underground doesn’t sound like a great idea, and by and large it wasn’t. Platforms were always very hazy and smoky, it can’t have been good for anyone’s health, and the lines themselves had to have regular open air points so the worst of the smoke and steam could escape to the outside world. This requirement gave the street of Leinster Gardens a bit of a claim to (nerdy) fame. It’s a fancy street full of lovely white Victorian terraces, uninterrupted for ages. It’s only when you look a bit close that you see something I little odd about number 23 and 24. Their front doors don’t have letterboxes, and instead of glass in the windows they all look quite solid and grey. The unsurprising reveal here is…that’s because they are. The train line had to go under Leinster Gardens, but also needed space for let steam out. So the facades of 23 and 24 Leinster Gardens are just that – facades, just 5 ft thick to the give the illusion of an a fancy street of uninterrupted terraces, with nothing behind except a big drop down to the railway line. The fact there are now huge trees in front of them also hides the effect (and probably deters the train nerds! 🙂

Anyway, this little railway they built was quite successful, word got out, other people wanted in on the money that was flowing and so many business-folk started building their own railways. Often right next to existing ones just to hopefully siphon off some of their customers. I guess in the late 1899s half of London must have had it’s streets ripped up as everyone tried to build train lines to everywhere. Gloucester Road still has a really good example, with two (formerly) competing train lines having stations right next to each other.

They were completely seperate, competing companies – if one company got you part way to your destination but you needed a different one to complete the trip, that meant a seperate trip up to the other company’s ticket office, and paying for another ticket. I can’t imagine that would have been in the slightest bit frustrating – especially when there were 5 or 6 companies just for tube lines alone. But of course all that mattered was getting a share of the money, nothing to do with having any concern for the customer experience or how they might get from A to B if their journey needed trains from more than one company.

As years (nearly 40 of them) went on, underground space became limited, the only option was to go deeper. This also meant steam was not an option, as there was no way to get it out of the deep-level tube and into the air above. As luck would have it this was around the same time as the first experiments with electric trains which, by 1890, became a viable and successful option, giving these ‘deep-level’ companies an edge over their competitors, as their trains were smoke free, their platforms were smoke free, they even rammed the point home by cladding stations in all white tiling, to show how it wasn’t being marred by smoke and soot. Of course, in time, all the other tube companies running the shallower lines followed suit.

Fast forward a bit and eventually everyone could see that all these competing companies was just a dumb idea when it came to the customer’s experience. So the whole lot was nationalised (or at least London-ised), and treated as me big london-wide travel network rather than seperate competing companies. Lines that were close together had walls knocked through of corridors built so it was easy to get from one to the other. Surface buildings were merged (like at Gloucester Rd) so one entrance covered both lines. It makes much more sense. But it does help explain why you just never know what you’re in for when you change from one tube line to another at any given station. Sometimes it’s a straightforward short walk. Other times, because originally these train lines weren’t built to be interconnected, it can be an escalator up, stairs down, then another escalator, then a corridor, more stairs, and then two sets of escalators… they found a way to make it work but we’re stuck with short-sighted decision made over 100 years ago. But for me, all that randomness and inconvenience is a part of its charm. When you set off from one line to another, you don’t know if it’s going take 30 seconds or 5 minutes. Every time is a little adventure. There’s a thoughtful interchange at Green Park between the Piccadilly (blue) and Jubilee (silver) lines – the corridor is very long, white with blue and silver small tiles peppered throughout. But as you travel from the Piccadilly end to the Jubilee end, the amount of blue tiles starts to reduce as the number of silver tiles increases – giving you some impression of that the fact that no this isn’t an endless corridor, you are actually making some progress, and hopefully in the direction of the train line you were after .

There’s a bunch of ‘axonometric’ (no I don’t know) diagrams of some stations, here’s one that might help illustrate some of that complexity when changing from one line to another. Unlike Sydney (until recently) there’s also a change in trains – the barely-undergound ones are normal size, the deep level ones are much smaller, with the doors curving up at the top ready to chop the heads off unsuspecting tall people who don’t move right inside. And this is after they were widened a long time ago, so the initial experience would have been super cosy. There’s an old carriage at the transport museum, the ‘padded cell’ – so called because the designers figured that when you’re underground you don’t need windows, so it barely had any. You just relied on the guard to yell out which station you were stopped at.

Design has long been an important feature of the tube – people need to know where to find it, and as the companies were all brought together as one entity, the ‘underground’ branding with its famous red circle and blue stripe was established. We’ve all seen it, it turns up everywhere – including, at Gloucester Road, on every single stair step.

I love the old design features on the Piccadilly line – starting with the above-ground buildings. Very distinctive, why not say iconic, their familiar oxblood-red tiles and arched windows are very distinctive. Leslie Green the architect sure knew a thing or two about branding even back then. I don’t know how many of these beautiful stations there were initially (because I’m typing this on the plane and I don’t have internet) but there are still about 45 of them left.

Back in the day, protecting heritage and preserving history wasn’t as bit a deal, compared to the progress of technology. Initially in the early 1900s as deep-level tube lines like Piccadilly were being opened, the only way to get there was by lift. This of course could be time consuming, a lift from the platform to the stations isn’t going to hold a train full of people, so it could take a while to get to the surface… something we experienced once or twice at Covent Garden, and on the Piccadilly Line at Gloucester Road. This means that yes the tube pre-dates the invention of the escalator, which came around in about 1911. It was obvious that the escalator is much a much better solution to moving passengers, and so they were retrofitted where possible. However, much of the time this meant the surface building and ticket hall had to be moved, since the escalator didn’t come out directly over the platforms like a lift would. So a number of surface buildings were just knocked down and new entrances built to line up with the escalator- either a newer smaller building, or just a hole in the footpath with stairs, New-York style. It’s the right thing to do, but without regard to preserving what was there, I guess a fair bit of heritage was lost. Still, you can’t stop progress, the whole system wouldn’t be workable if it still ran on lifts and lifts alone.

Below ground, the Piccadilly line stations have some lovely design features – the station names were glazed into the tiles, and each station had its own tile colour and pattern, allegedly done so that even all those people that couldn’t read back in the day still had a good chance of knowing which station they were at.

Initially each company had different ways of designing their stations but I’m glad they didn’t decide to go and fully standardise everything, giving the Piccadilly line that bit of extra charm. It’s great that some stations still have some individuality about them – Euston for example has some tile work showing the giant arch that used to be at the front of the station before it was pulled down in the 1960s. Green park has a tiled mural of autumn leaves. The more modern platforms of Baker St have a Sherlock Holmes motif running across them. Leicester Square has tiling to simulate a filmstrip running all the way down the platform, being as it is the centre of the big movie premieres. Embankment has an abstract colourful theme done in 1986. There are heaps more no doubt that I didn’t get to see. Even the old ‘Way out’ and ‘No Exit’ tilework signs are just beautiful.

Some other stations are just huge standouts in and of themselves, design-wise. I’m still kind in awe of Westminster station on the Jubilee line, with its cavernous void and unashamedly modern grey industrial look – I’m sure it’s weird to be so appreciative of a void, like, a bit area where stuff isn’t, but it really grabbed my attention, I still have’nt taken photos that I believe capture it properly, and for whatever reason I still just love it coz it feels so out there.

Nowadays, the less interesting but more obvious yellow ‘Way Out’ notices everywhere are extremely helpful, when it comes to navigating some of the weirder station layouts. It’s this consistency that gives the network some strength, knowing that consistent signage across the whole network means you can trust it to get you to where you need to be. Each of the lines is colour-coded, and the tube map is world famous for the way it ignored the actual layout of the city to make the maps itself so much more readable. The only trouble is now there are so many lines, sometimes it’s hard to make out one colour from the next.

Accessibility is still an issue and I guess will remain one for some time. In the 1800s and at least early 1900s, less mobile passengers weren’t considered at all, and if a station offered step-free access, it was by chance, not by design. Lots of remediation work has been done since, but even now only about 1/3 of tube stations have step-free access. (Something to consider when you have a metric but load of luggage, too). At least all new stations being built are of course made with step-free access in mind.

Then, there’s the new Elizabeth Line. Long delayed, but fortunately opened while its namesake was still around, it is an ambitious new forward thinking line going east-west across London. It’s been built to be as future proof, and as pretty, as possible. There’s a whole bunch of clever stuff around signalling technology or something that can get trains through every 2 minutes which is pretty impressive, but it’s the scale and, well, beautify of it that impressed me the most. I only had a very quick visit and travelled between two neighbouring stations, but man, based on that very small experience they really seem to have got it right. The platforms are huuuuuge, somewhere around 300 metres long. So the trains are very long as well, with tons of capacity. The stations have those doors along the platform edge so you can’t fall onto the track. There’s a ton of room on the trains, the platforms, and the interconnecting corridors – everything feels like it’s built on a scale 2 – 3 times bigger than the tube lines. And it’s just really, really pretty. They go to great pains to point out that apparently it is not a tube line, it’s a new “transport mode”, or something. Still goes through a big circular hole in the ground though, kinda, you know, tube-shaped. Anyway I’ll let few photos I took do the talking.

Now I don’t expect anyone else to be all excited about a bunch of trains running under London. You’ve got people like Geoff Marshall and Jago Hazzard whose YouTube channels explains things better than I ever could. But I’m glad I got to travel around, visiting stations old and new, the whole system never let us down once despite strikes and so on, we never once waited more than 4 minutes for a train. Sometimes, it’s the journey itself that matters – perhaps even more than the destination. Mind the gap!